FAILURE

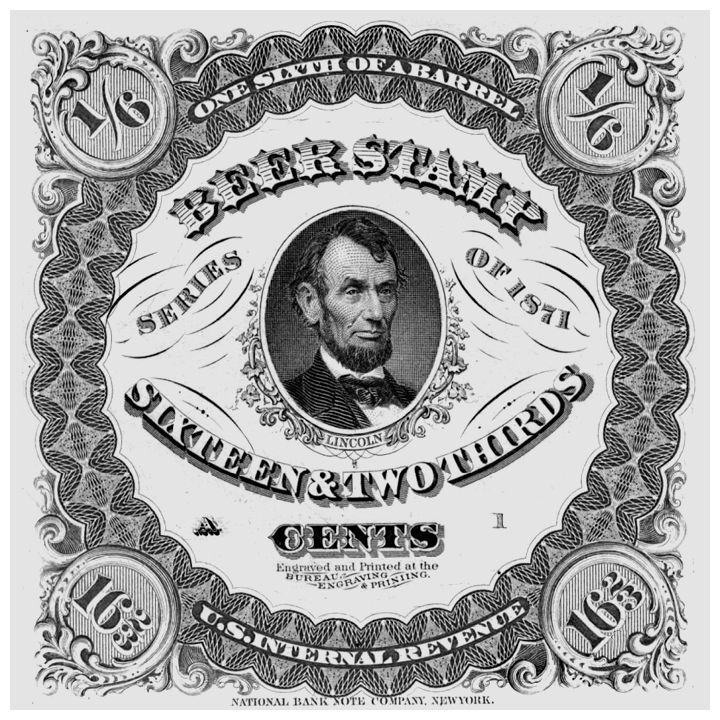

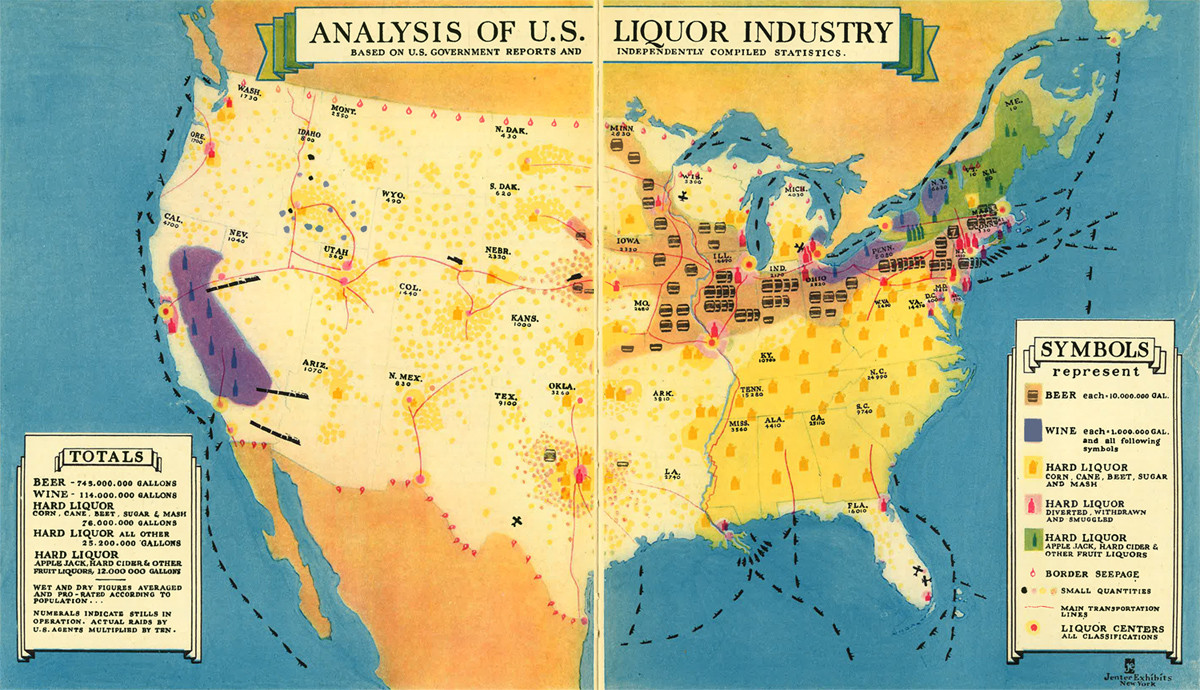

Liquor and beer taxation began in 1862 to help finance the Civil War. But the tax revenue from the beer industry also supported the nation itself, especially after the war.[1] The German brewers responded to their new national influence by founding the United States Brewers Association. Brewery workers who were not included in this association also felt a new national identity and were among the earliest laborers to organize into a union.[2]

While breweries contributed a massive amount to the federal government by means of taxes, liquor distillers responded to taxation with evasion and fraud. [3] The German brewers looked “back in fondness at the respect and support German governments accorded beer”. [4] They hoped to encourage a similar positive relationship in the US and were willing to “accommodate themselves to the IRS”.[5] Thus, they were more flexible in accepting the government’s influence than the liquor distillers. But, they expected respect and trust in return.

The relationship between the brewers and the government was one of the first examples of business mixing with politics. And one can better understand the Gilded Age and rise of the corporation by examining the USBA’s lobbyists. The liquor industry contributed over 50% of the federal government’s internal revenue from 1875-1894.[6]

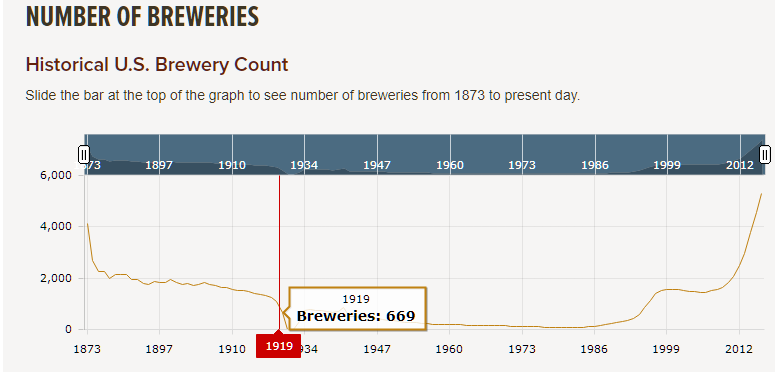

In the early twentieth century, brewing was the fifth largest manufacturing industry.[7] The brewers thought they were ‘untouchable’.[8]

And they were: until Taft proposed the 16th amendment implementing the federal income tax in 1909. Suddenly, the brewers’ taxes were not as important.

And then came the 18th amendment: Prohibition.

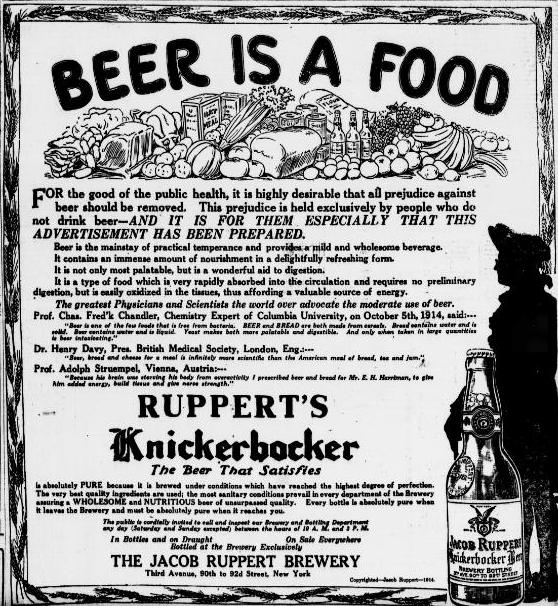

The prohibitionists were outraged by the federal liquor taxation as they believed it gave legitimacy to the industry.[9] When the Temperance movement was mostly directed at the saloons and hard alcohol distilleries, it initially helped beer sales as lager was used to replace over indulgences in hard liquor. Therefore, the brewers thought they would be immune from Prohibition.

The brewers also felt safe because many of the brewers held office and because the average consumption of beer for an adult in 1917 was thirty gallons!

The growing Temperance movement often missed its mark and instead of attacking alcohol, they condemned the immigrants who brought a culture of drinking with them. Immigrants often suffered from a higher level of alcoholism, due to reasons that went well beyond mere cultural preferences. It was not because they were Irish or German, but because alcohol was often used as a refuge from the poor immigrant’s tough existence of extreme poverty and dangerous factory work. Many of these immigrants worked in the breweries. The brewers hired unskilled immigrants who worked long hours for seven days a week. It was a hard life and many suffered from arthritis and respiratory issues from the temperature changes occurring when a worker traveled between the warm brewhouse and the ice storage areas. They used the drink as a way of escape. Temperance advocates misidentified the heavier drinking of the poor immigrant, blaming it on their nationality or culture, rather than the harsh conditions of their lives. This anti-immigrant sentiment caused Temperance supporters to seek to impose restrictions on immigration. This led to discrimination against the lower social classes.

Another target of the Temperance Movement was the saloons. Saloons were financed by brewers offering the customers free, salty food that increased thirst. As the consumption of distilled spirits increased, it caused problems: domestic violence, crime, neglected children, financial woes, disease, and death. It was these combined effects of alcohol abuse that led reformers to warn against ‘demon rum’ in a concerted program to influence policy often referred to as pressure politics. First, temperance encouraged moderation; then came pledges for abstinence; finally, came the invasive demand for closing of saloons.

In the pursuit of this goal the Women’s Christian Temperance Union became a powerful pressure group, second only to the Anti-Saloon League (1895) which controlled state legislatures and elected officials; they were a threatening influence over the Presidents through congress. They set well-defined objectives that changed the laws in increments, and they reached each one. Under this campaign, nearly half the area of the United States went dry by 1913. In New York alone, league efforts had increased the number of dry towns from 276 to 400.[10]

Although, the Temperance movement began its drive towards federal prohibition in 1913, they were not entirely successful until the entrance of the United States into World War I. Participation in World War I led to anti-German sentiment which affected German-related industries. Beer became a particular target of anti-German indoctrination because beer used hops and grain which the government was trying to preserve to ensure that there would be enough cereal. Cereal was used extensively to feed the troops at that time. The Temperance Movement used the war as an opportunity to manipulate the masses and address the national emergency caused by shortages of vital goods. They circulated propaganda meant to shame the public by asking what was more important: Booze or Coal? The Prohibition advocates were unrelenting in their objective and brusquely reminded people of the connections between the brewing industry and the Germans.[11]

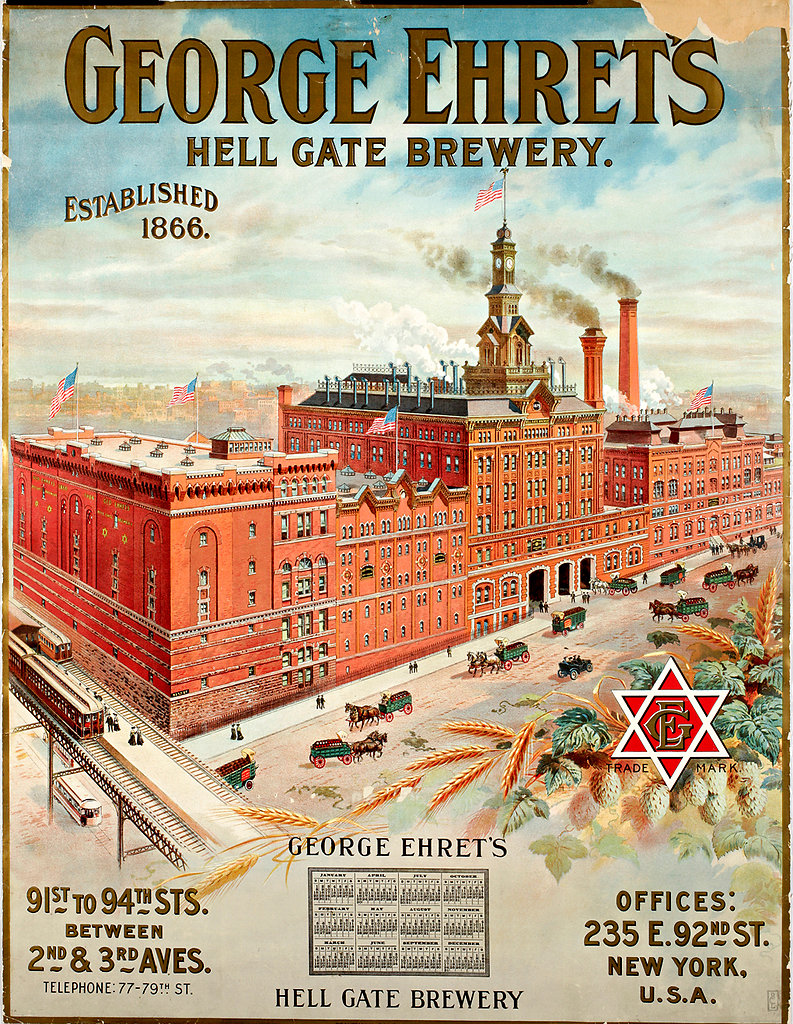

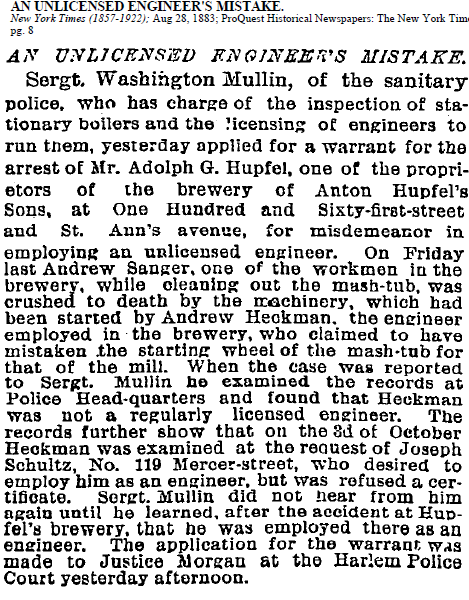

George Ehret of Manhattan’s Hellgate Brewery who was trained as a brewer at the Hupfel Brewery in the Bronx had his entire estate seized, all finances and businesses, by the Alien Property Custodian while he was on his annual trip to Germany. All his children were American citizens –he even refused to buy German bonds while in Germany where he was stuck due to illness and the war. His son went so far in improving his American loyalties as to purchase $2,000,000.00 in Liberty bonds, and Ehret promised to buy more once their estate was returned; yet, he was treated like a traitor. When he was finally able to return, “Mr. Ehret went on to say that he had been a citizen” of the United States “for over fifty years” and “his sympathies were entirely with the United States in this great war”. [12] When Ehret passed in 1927, he left his family a fortune ($40,000,000.00)!

Many of the women involved in the Christian Temperance Movement were major proponents of women’s suffrage but their demands went far beyond the right to vote; they became the representatives of the standardization of morality. They considered prizefighting, slang, prostitution, and especially alcohol to be considered immoral. The Anti-Saloon League argued that there was an unethical coalition between bars and politicians, and they were correct. The New York Public Library has digitized several menus from the Ebling Casino where politicians threw lavish parties and held important meetings. Also, several of the brewers held political office. The Ruppert family, one of the biggest brewers around, even owned South Brother island where they entertained influential businessmen between 1890 and the early 1900’s.

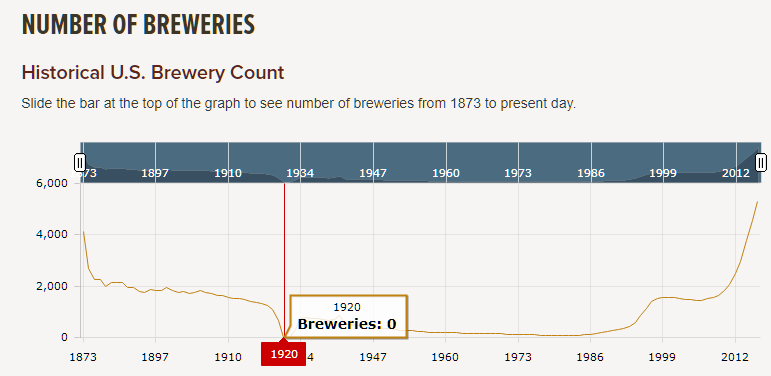

The Eighteenth Amendment authorized prohibition. To enforce it, the Volstead Act came quickly, and took the most extreme form possible, outlawing even beer and light wine (except for sacramental purposes), and ridiculously defining as “intoxicating,” anything with over .5% of alcohol.[13]

With the implementation of Prohibition and the Volstead Act, (October 28, 1919) the industry was doomed.

The Bronx was brewing until Prohibition caused the downfall and subsequent destruction of one of the most successful industries in the country.

The eighteenth amendment authorized Prohibition in December of 1918. After December 1918, breweries were not allowed to produce beer, but they were still allowed to sell their inventories. However, after July 1919, they were not even allowed to see beer at all.

When federal prohibition arrived, those breweries which were more likely to produce alternative products, survived. Prohibition meant the end of many small, local Bronx breweries. The larger breweries with more of an investment to lose, were not as motivated to abandon their brewing business.

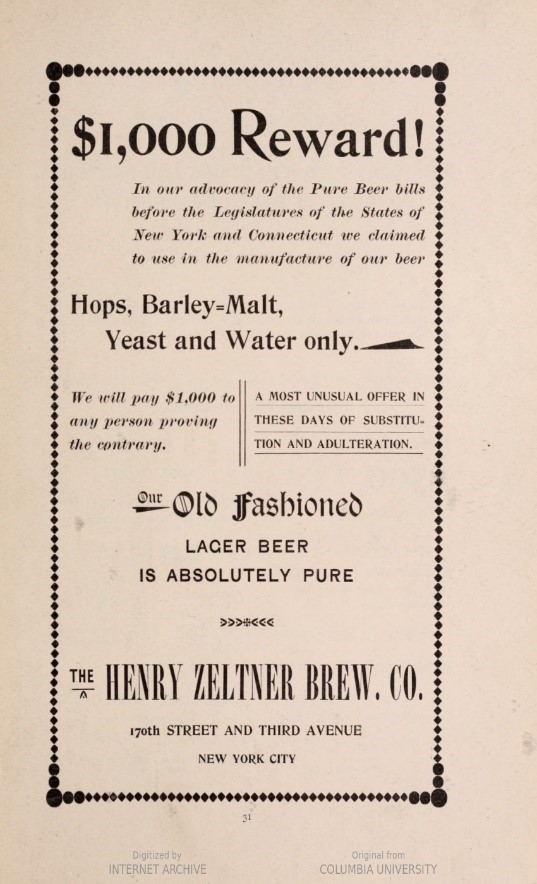

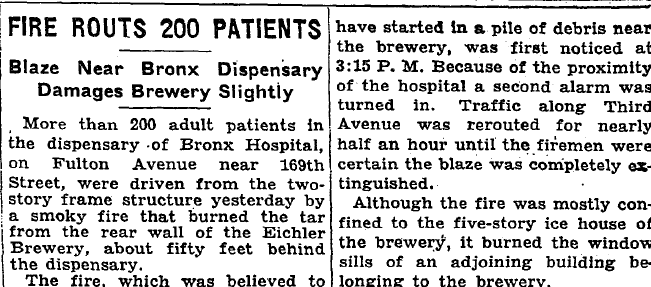

Breweries survived federal prohibition by switching to other products that shared technologies with the production of beer. Most of the breweries closed; the others survived by producing ‘near-beer’, becoming dairies (their refrigeration technology was perfect for ice cream), selling malted products, and in one case, becoming a mushroom farm (Hupfel Brewery). The Haffen Brewery, Mayer’s, and Northside closed, and Zeltner’s followed suit not too long after. Only three of the remaining Bronx breweries from that era continued to brew beer, near-beer that is, with half a percent of alcohol: Eichler’s, Ebling, and Mayer’s.

As it has already been made clear, cities that were associated with the changes in economy and values, were populated with people who were from older, rural societies and were quickly becoming increasingly modernized. But modern thought is not always anti-traditionalist. Often, the rise of the modern city created opportunity, as well as anxiety and confusion.[16] The public’s new ideals were a direct result of technological advancements that transformed the urban environment, thus, changes in values were a by-product of industrialization, not vice versa. Society was adapting to the effects of massive technological improvements and developments and the impact those had on urban life. One of these impacts was the emerging middle-class and the new neighborhoods needed for them to live. There was also an emphasis on the growth of urban development.

Industrialization and urbanization expanded in New York. Manufacturing that used machines plus a labor force increased production, encouraged development, and led to the encouraged development neighborhoods grew in both population and size. The area became more concentrated which accelerated economic activity, thereby producing more industrial growth. The City’s economy was still based on manufacturing: an economy which employed approximately half of New York’s immigrant workers. However this would change after World War II.

The declining beer industry caused the loss of working-class prominence in the City. “At the end of World War II, New York was a working-class city”.[15] Most of the city’s 3.3 million inhabitants were blue collar workers in the mid-1940s. However. it was around the same time that deindustrialization and an economy based more on financial and other services rather than production and manufacturing began a process that eventually devastated the Bronx’s blue-collar labor force. At the time, many viewed these developments as positive, as it was a natural transition of workers from blue collar to white collar industries. “By the end of the 1960s, white collar workers outnumbered blue collar employees two-to- one.”[14] This led to declining city revenues and populations, as well as many businesses that fled the city taking their revenue and jobs with them.

The Bronx was Burning

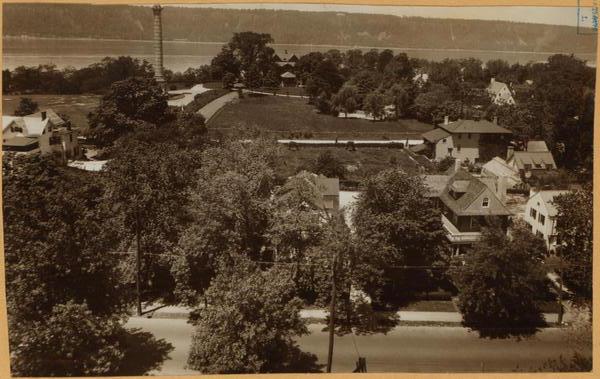

Geography has always dictated the Bronx’s course and thus, the trajectory of the Bronx. It was not only the rise in crime and overcrowding of lower Manhattan that led immigrants to migrate to the North side. “It was the search for air and sun that led to the migration from the Lower East Side . . . to the quiet streets of . . . the Bronx.”[17] The Bronx was a suburb within the city-limits. If Manhattan is the Big Apple then the Bronx was the Green Apple; with over 25% of space dedicated for parkland, an abundance of affordable apartments along with easy access to work in Manhattan via the el, the Bronx offered an opportunity for a better existence. The wide-open spaces of the Bronx inspired Manhattanites to push northward, migrating away from the congestion downtown.

It provided a safe-haven and fresh air.

In post-Depression era New York, the city’s infrastructure was crumbling, corruption was rampant, and essentially, the City did not function as it should. At the time, more than 10,000 of the 29,000 manufacturers closed their doors in NYC. Those who were not unemployed were underemployed. The effect on the children was horrific: 60% of clinic work was helping malnourished children. The population was rising and the budget rose with it as debt increased –and Tammany was its usual shady self. City employees’ salaries were cut, public works were nonexistent, the police were bullies and the city was failing the people by not meeting their needs. Because tax dollars went to salaries of Tammany’s people, there were no civic improvements. Construction pay offs made it nearly impossible to get anything done.

REDLINING

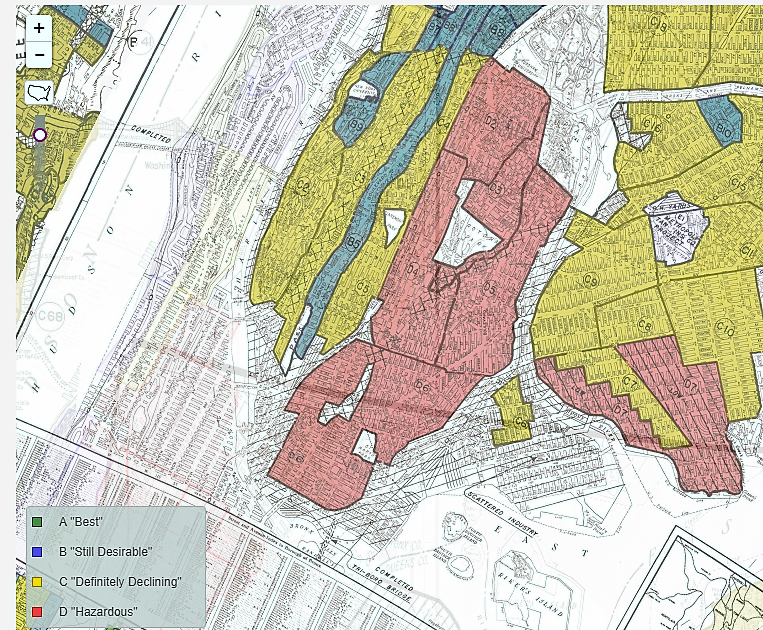

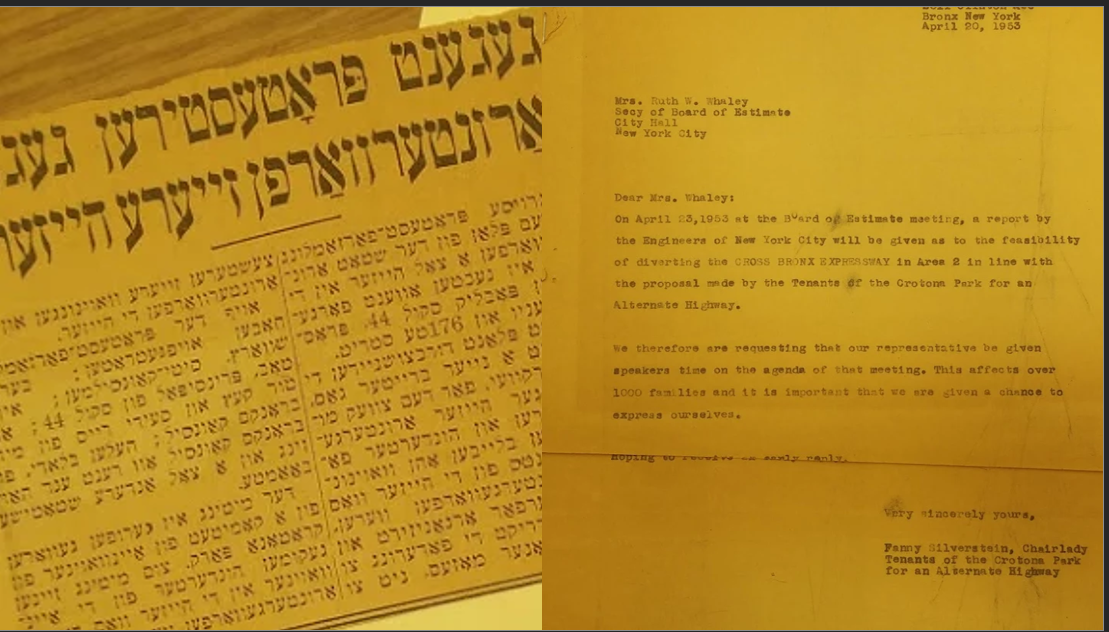

De-industrialization of the Bronx began with FDR’s New Deal era’s National Housing Act of 1934. Home Owner’s Loan Corporation was asked to investigate hundreds of cities and they created racially biased maps that graded desirable and declining areas. The redlined sections were considered too risky for real-estate investments.

These areas were disqualified and were usually the oldest neighborhoods, like the south Bronx, and where the majority of residents were people of color. This is when the infrastructure started to crumble. The maps were used as a resource by federal agencies, banks, real-estate investors, and businesses to disqualify the south Bronx from future investment.

When The Power Broker was published in 1973, Robert Caro took advantage of the depressed emotional climate of NYC. The city was in despair and on the verge of bankruptcy.

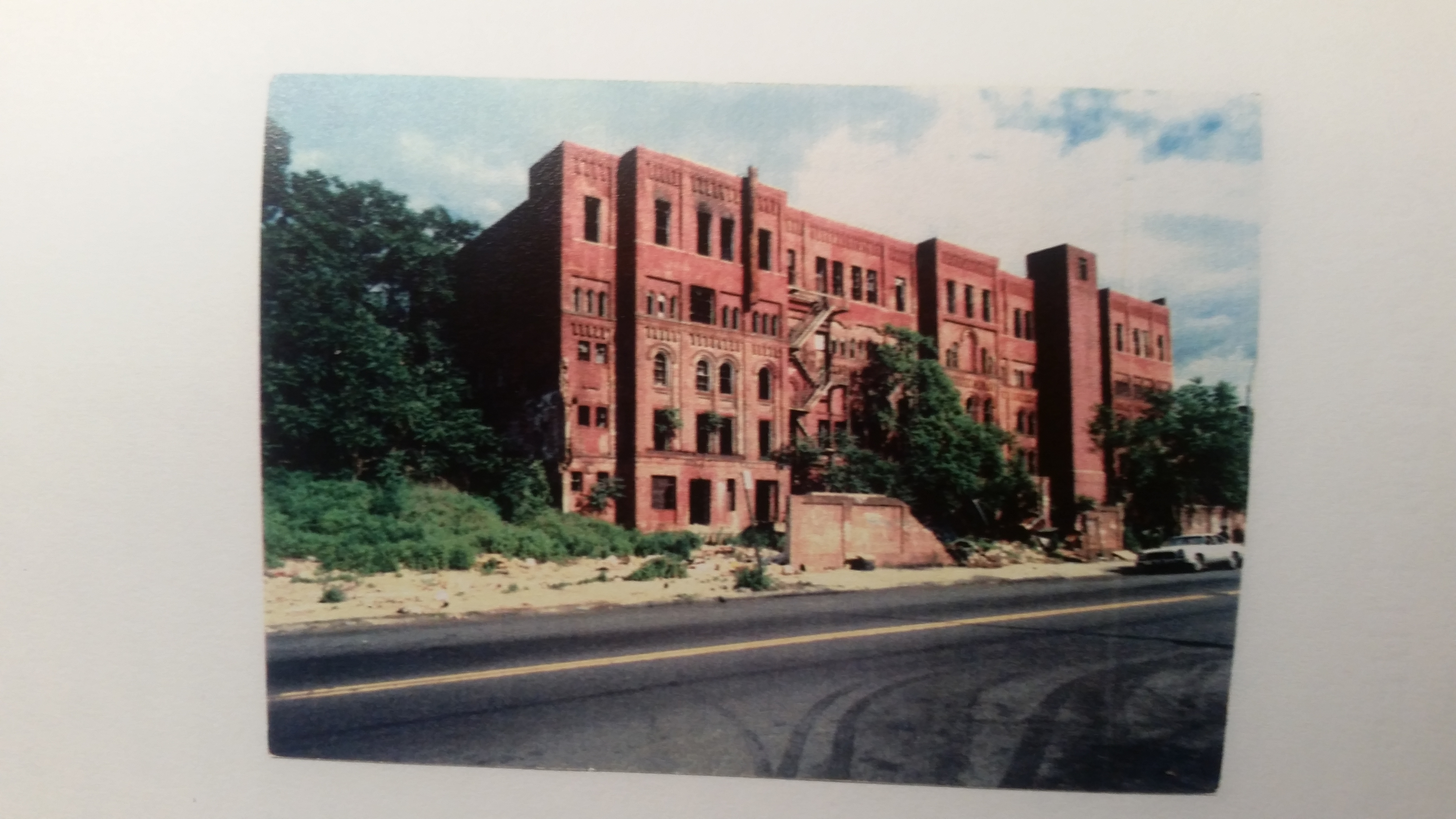

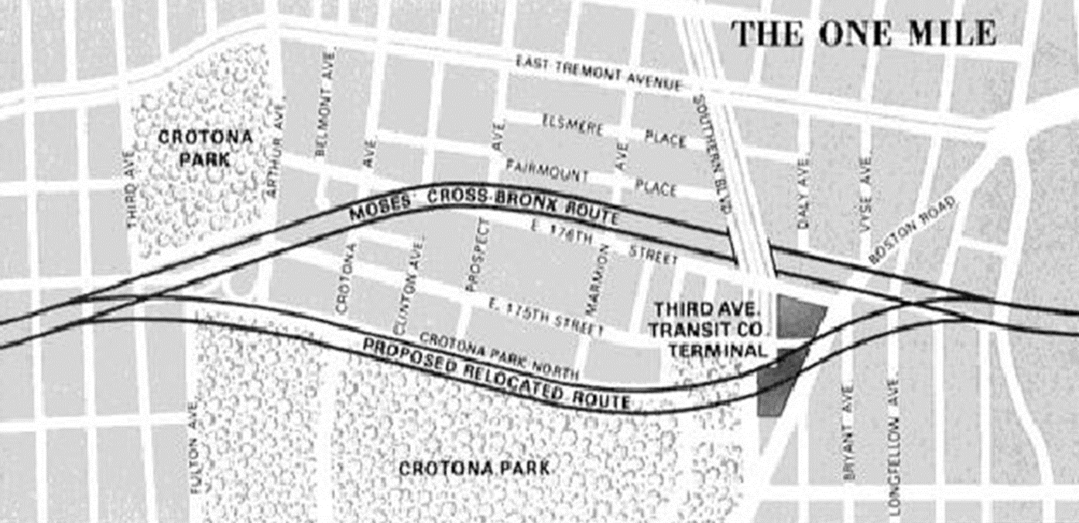

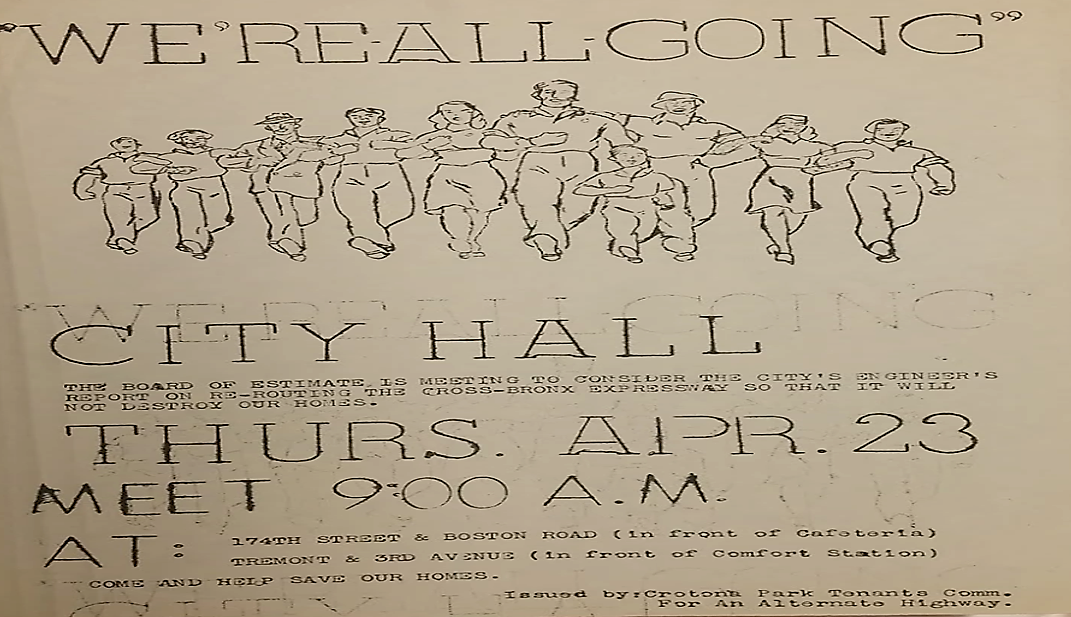

The blighted neighborhoods of the Bronx were soon burning. Many blame the Cross-Bronx Expressway, seeing it as a marker for the beginning of the Bronx’ downfall.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway is not solely guilty of the urban blight of the Bronx.

There were multiple factors: disinvestment in the community, the aforementioned federal redlining of the south Bronx, Mitchell Lama middle-income housing like Co-Op city that siphoned out the remaining white families of the Bronx, and neglect. That, and the federal government’s guaranteed housing loans that favored the suburbs and the expressways that brought you there faster also led to small business closures and urban decay.

New developments like Co-Op city and the modern high rises of Riverdale attracted the Bronxites just as Parkchester lured them in the past. The older apartments in the South Bronx had antiquated electrical and could not handle modern technologies, there was a decline of services, and buildings fell into a collective state of disrepair. Everything was built at once and thus, it was only natural that it would start to deteriorate simultaneously.

And people wanted air conditioning.

“Tear down the old, build up the new. Down with rotten antiquated rat holes. Down with hovels, own with disease, down with firetraps, let in the sun, let in the sky, a new day is dawning, a new life, a new America.”

—Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, touting slum clearance and the construction of public housing

The lower to middle-classes began to take their businesses out of the Bronx; industry was fleeing and thus, their tax-dollars as well. So, not only was money not coming into the Bronx, it was not being spent, or invested in the Bronx either. And now, entire neighborhoods were eradicated, uprooting people with the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway which callously bulldozed through and gouged huge wounds that used to be neighborhoods. Robert Moses provided housing for thousands of tenants, but the housing erected to replace the tenements (and often, not-so “tenement”, but beautiful pre-war edifices) that were torn down was geared towards the middle-class and more affluent, not the poor. Thus, the evicted tenants who could not afford the new housing had no option but to move to the congested slums of other areas, or areas on the cusp that were eventually shoved in a negative direction.

In The Push and Pull Dynamics of White Flight: A Study of the Bronx between 1950 and 1980[18], Megan Roby investigates what caused the majority of the white citizens to leave the Bronx so quickly. She focuses on the changing racial demographics of the Bronx and argues that it was a push (drugs/crime) and pull (suburban/modernization) that caused the mass exodus. She asserts that a change in demographics is not unusual, but such a dramatic change in so short an amount of time, 50 years, is. Roby explains that the drastic change was a combination of a push and pull that led to the mass exodus of white ethnics and perceived racism against the Hispanics and Blacks who were moving in. But, it was the combination of the lure of the suburbs, the push of local drug use and rising crime that drove the white ethnics, out of the Bronx. The war on drugs became attached to those with lower incomes. She speaks to former Bronx citizens because she feels that in order to understand the emotional climate of the borough, one must speak to those who witnessed the change to better understand their motivations for leaving. [19] She argues that in the south Bronx, children were raised with geographic borders; one feared travelling outside of these boundaries for it could be quite dangerous creating class formation and slum neighborhoods. The tax incentives were for the suburbs, the city was bankrupt, services were cut, homelessness, crime and drug use were on the rise.

Many blamed race on the deterioration of the Bronx, but it was not the true culprit: the economy.

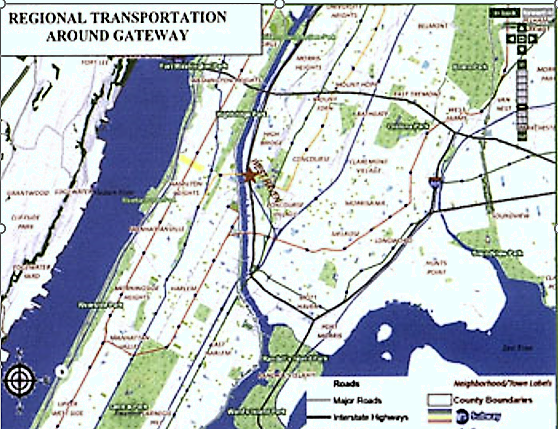

The same transportation that enabled the growth of the Bronx, also contributed to its demise by allowing a new suburban commuter society to grow. One could live in upper Westchester and still keep one’s city job. Inexpensive homes, special financing for veterans, low-rate mortgages pulled people to the suburbs.

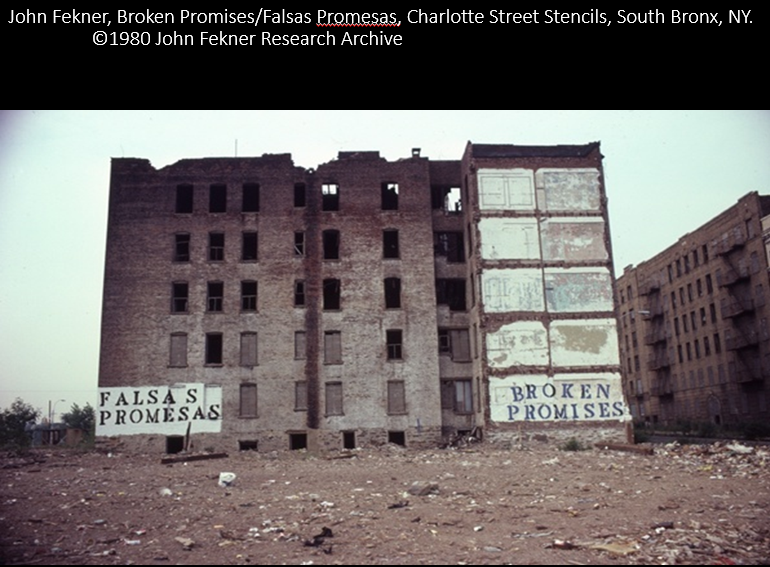

And then the Bronx began to burn.

As the residents of the South Bronx left, black and Puerto Rican residents took their places. Many of these tenants were out of work and living on welfare in rent-controlled buildings. The landlords were losing money on their investments and many wanted to walk away from these burdens; the owners became aware that they could make more money with insurance, so they would hire local thugs to destroy their properties by fire. It was a perfect crime as the fires were never investigated; there were too many. Eventually, the tenants joined in on the insurance fraud learning that they would be moved to the top of the tenants list for new public housing. Novelist and former firefighter John J. Finucane recalls that “collectively there we did over 35,000 runs in one 12-month period I’m not talking about garbage cans burning, I’m talking about two rooms, three rooms in an apartment, or maybe two floors, or maybe the whole damn building. Some 350 people a year were dying in these fires, with six to 10 of them including firemen.”[33]

RENAISSANCE

As previously mentioned, the Bronx’s proximity to Manhattan and its growing congestion, overcrowded tenements, and violence provided a canvas equipped for the expansion of the rail and subway, changing the Bronx to a land of commuters and full-time residents, not just elite visitors. Before the elevated train gained access to the Bronx for the masses, most people only visited. With its borders consisting of the Hudson and Harlem rivers, the Long Island Sound and its beautiful rustic landscape it was a desirable destination for the affluent –who were the only people who could afford their own transportation. In the beginning, the Bronx provided the space needed for industry and with almost twenty-five percent of the land mass reserved for parkland, the rest of the borough was prime real estate for urban planners to utilize the grid system in some areas and abide by the natural landscape in others, offering the best of both worlds. It was perfect for future residents’ homes, universities, and commercial ventures. Although the hilly west Bronx’ hills may have hindered the capability of a grid system, –unlike the east Bronx and Manhattan— natural ridges provided prime real estate for a grand boulevard (lager caves) and its valleys, Broadway, Jerome, and Third-Avenue, perfect for retail and the els. These grand roads were also needed to connect the parks of the area that were not being utilized to their potential.

By the 20th-century, the once “thriving industrial center formed the western edge of one of the poorest sections of New York City . . . a section that would languish in blighted obscurity for almost 60 years.”[34] For over 50 years the rehabilitation of the South Bronx was stalled by perceptions that the South Bronx was “economically, architecturally and socially unsalvageable.”[35] The use of strategic cooperative development expanded local economic capacity within one of New York City’s most blighted areas. Today, an example of successful urban-renewal projects like Gateway at the Bronx Terminal Market, generate revenue within an environment of general community support and ecological sustainability–affirming New York City’s commitment to rebuild its much-maligned older core. Early regional patterns of transportation around the Gateway project area remained operational, despite the physical and economic deterioration experienced by this community since the end of World War II.

In There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up, Lance Freemen delves into Inner-city perceptions of “gentrification” and dissects the process of gentrification –what it is, how it happens, why it occurs, and who is affected.[20] The reader learns the extent to how much these one-time slums of New York City have evolved with gentrification. Evolved, not devolved. The research goes against some of the common wisdom (or outright myths perpetuated by fear) regarding gentrification in the inner-city. Many new buildings have been rising in the South Bronx, many affordable. But, because the south Bronx is a real estate developers dream, with waterfront property available, and short commute to Manhattan, there needs to be more incentive for affordable housing as well. Unfortunately, with the massive amount of public housing in the Bronx, it is unlikely that the Bronx Renaissance seen in SoBro, will reach inland any time soon.

What we have learned is that gentrification is neither good, nor bad; it has its challenges and its opportunities[21]. Surprisingly, statistical results do not support the common belief that “gentrification” is displacing the locals from their homes; in fact, the counter-intuitive results proved that gentrification effectively lowered mobility of the lower-income tenants, an important characteristic not usually recognized in academic literature.[22] The study soon morphed into an enquiry of how residents truly experience gentrification and what Freemen calls, an “accidental ethnography”. The answers found to questions raised by empirical data and the evidence obtained were contrary to the familiar depiction of residents as victims of gentrification.

Previous scholarship was accustomed to focusing on the legitimate societal pathologies connected to gentrification: government neglect, redlining, disenfranchisement, drug epidemic, discriminating whites, deindustrialization, job loss, the Depression, World War II, disinvestment, even the complaint that no new housing had been built except for public housing projects that only further concentrated the poor, for the causes of the decline. It was found that earlier studies were flawed; they only studied displacement during gentrification, not earlier, when there wasn’t any. Thus, it was impossible to thoroughly compare results. If gentrification is only studied from a neo-Marxist perspective with a class-conflict focus, of course the loudest voice will be heard, and it does not necessarily represent all the voices of the neighborhood. In fact, they are probably atypical of the rest of the area, ergo, their alarm with whatever redevelopment is anticipated. Scholarship focused on political noise and, thus, offered an uneven representation.[23]

Gentrification needs to be observed by more than a displacement vantage-point; it should include the social interaction of the indigenous vs. gentry and what those implications are. Whereas the sociological approach focuses on how non-white residents relate across economic sub-classes, it should be contrasted with an approach that concentrates on how residents experience the process of gentrification, thus, illuminating the actual impact on the local population. The surprising results debunk the poverty deconcentration thesis and prove more of an acceptance from the locals. Residents were receptive, even optimistic, with regards to the bringing of mainstream culture and upward mobility to their neighborhood — as well as distrustful and pessimistic, simultaneously. There are gulfs of misunderstanding of gentrification; the chaotic nature must be studied from many angles and perspectives because gentrification impacts people differently.[24]

Many would argue that improved services arrived when the whites started returning to the South Bronx. It would not be untrue. But it does not mean that they are there to take advantage of the poor to displace him or her. One could posit that the people moving in might have a higher socio-economic status, but they are moving to “the hood” because they are often getting priced-out of other neighborhoods. The problem is that the negative myths attached to gentrification have “just enough truth to make it credible”[25] It is easier to believe some of the gentrification myths because there are so many credible examples of horrific treatment of non-whites.

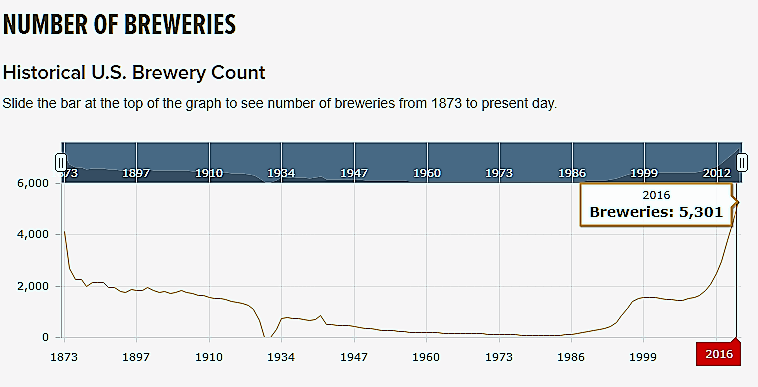

“The American brewing industry reached another milestone at the end of June, with more than 3,000 breweries operating . . . Although precise numbers from the 19th century are difficult to confirm, this is likely the first time the United States has crossed the 3,000 brewery barrier since the 1870’s . . . the Internal Revenue Department counted 2,830 “ale and lager breweries in operation” in 1880, down from a high point of 4,131 in 1873 . . . While a return to the per capita ratio of 1873 seems unlikely (that would mean more than 30,000 breweries).”

The Bronx lost over a half a million factory jobs between 1947 and 1976[26] and in 1960 civil service jobs opened up to those living outside of the city which increased competition for positions with an already deteriorating job market, an influx of minority families, along with the loss of business to the suburbs, the Bronx was doomed. The jobs that left were the jobs dominated by the minorities. By the late seventies, most of the Bronx was unemployed (30%), the city was destitute, and 1 in 3 were on welfare. With unemployment rising, many turned to crime to escape their situations through drugs. It was only natural that former South Bronx residents made connections between race and the rise in crime; but the real motivation was economic turmoil, not race. The ghettoization of minorities and the flight of the whites was caused by the policies of post war New York City. Low-income public housing created a forced segregation separating the whites from the Hispanics and Blacks physically, as well as culturally[27] which made racial tensions worse. Rumor and ignorance can create extreme behaviors when also forced to live with and also without the other.

Conclusion

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed HR1337 repealing the Prohibition-era embargo of homebrewing, and inspiring the current craft brewery craze seen around the country.

In 2014, Governor Cuomo passed the NYS Craft Act, the change in the law is part of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo’s five-year effort to simplify the state’s liquor laws, allow breweries to again sell by the glass, and eradicate inconsistencies and archaic regulations that were created after the repeal of Prohibition. When the state brewers’ association was founded in 2003, there were just 38 breweries in the state. Before that, brewers were limited to offering samples, usually free, and selling beer in packages to go. The breweries are starting to return. Today, we have three Bronx Breweries: The Bronx Brewery, Gun Hill Brewing Company, and Manhattan Brewery. Who knows how many more will be brewing in the future.

For a long time, the Bronx was known for its parkland, zoo, Botanical Gardens, schools, the Grand Concourse, and most of all, its industry. But, it is the burning Bronx that has offered the most indelible image of the borough. The Bronx is no longer burning; tenements have been restored, streets cleaned-up, subway cars washed clean of the graffiti, new suburban ranch homes built where rubble and trash used to litter the South Bronx; the Grand Concourse has even been declared a Historic District inspiring people to move uptown to a neighborhood they would not have even considered visiting, let alone living in. Yet, it is the image of the Bronx of over thirty-five years ago that is still summoned-up when urban decay is discussed in Detroit, or even in Paris –never the brewing industry. The New York Post reported that during a recent Paris mayoral debate the political hopefuls argued that Paris is starting to “resemble The Bronx” with its “rampant crime”, describing the North side as if it is lawless.[36]

It seems that the French are due a visit here.

[1] Joy Santlofar. Food City Four Centuries of Food Making in New York (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2016), 245.

[2] Amy Helaine Mittleman, The Politics of Alcohol Production: The Liquor Industry and the Federal Government, 1862 – 1900, Columbia University, 1986, 9.

[3] Mittleman, 2.

[4] Ibid, 5.

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid, 2.

[7] 1907 census

[8] Santlofar, Food City Four Centuries of Food Making in New York, 261.

[9] Mittleman, 6.

[10] https://www.oldnyc.org/https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics/economic-impact-data/

[11] Ibid

[12] “Ehret Expects to Get His Money Back” New York Times (1857-1922), Aug 13, 1918.

[13] Khermouch, Gerry. “Surviving the Ice Age. (Icehouse Beer; Marketing).” Brandweek 37, no. 10 (1996): 16.

[14] Lance Freeman, There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 168.

[15] Joshua Benjamin Freeman, Working-Class New York: Life and Labor since World War II (New York: New Press: Distributed by W.W. Norton, 2000), 6.

[16] Hays, 1,2.

[17] Ruth Gay, “Floors: The Bronx—then,” 1995. American Scholar 64, no. 3.

[18] White flight is a term that is widely acknowledged by the populace to label the phenomena of “whites” leaving en masse. Whenever possible, I will avoid this coinage. I would argue that White flight is specious in its simplicity; its usage effectively diminishes its constituents –who could be German, Catholic, Russian, Argentinian, Eastern Orthodox, Episcopalian, Italian, Albanian, Jewish, etc.– all of whom are unique and deserving of their own demographic. It is too broad a demographic and serves the agenda of others.

[19] Megan Roby, The Push and Pull Dynamics of White Flight: A Study of the Bronx between 1950 and 1980, 35.

[20] Gentrification is in quotes because I hate the term. I also despise the co-opting of “ghetto”; breeching imaginary walls won’t result in death as it did in the Jewish ghettos of Rome and Poland.

[21] Lance Freeman, There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 94.

[22] Freeman, There Goes the Hood, 5.

[23] Freeman, There Goes the Hood ,7.

[24] Ibid, 30.

[25] Ibid, 118.

[26] Roby, 44.

[27] Roby, 38.

[28] Hilary Ballon, Kenneth T. Jackson, Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007).

[29] Tenierello Papers, Lehman College.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Tenierello Papers, Letter to James J Lyons, Bronx Borough President, May 5, 1953.

[32] Robert A. Caro, “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York”(New York: Vintage Books ,1975), 860.

[33] Cahir O’Doherty, Why Did the Bronx Burn?” Irish Voice, November 21, 2007. 27.

[34] R. Rolston, Lorraine E. “A New Bronx Tale: Gateway Center and Modern Urban Redevelopment.”Focus on Geography, Summer 2012, 63+Academic OneFile (accessed December 27, 2017).

[35] Ibid

[36] Laura Italiano, and Kenneth Garger, “Snotty French whine: Paris becoming the Bronx”, New York Post, December 17 2013, page Six.