IMMIGRATION and INDUSTRIALIZATION

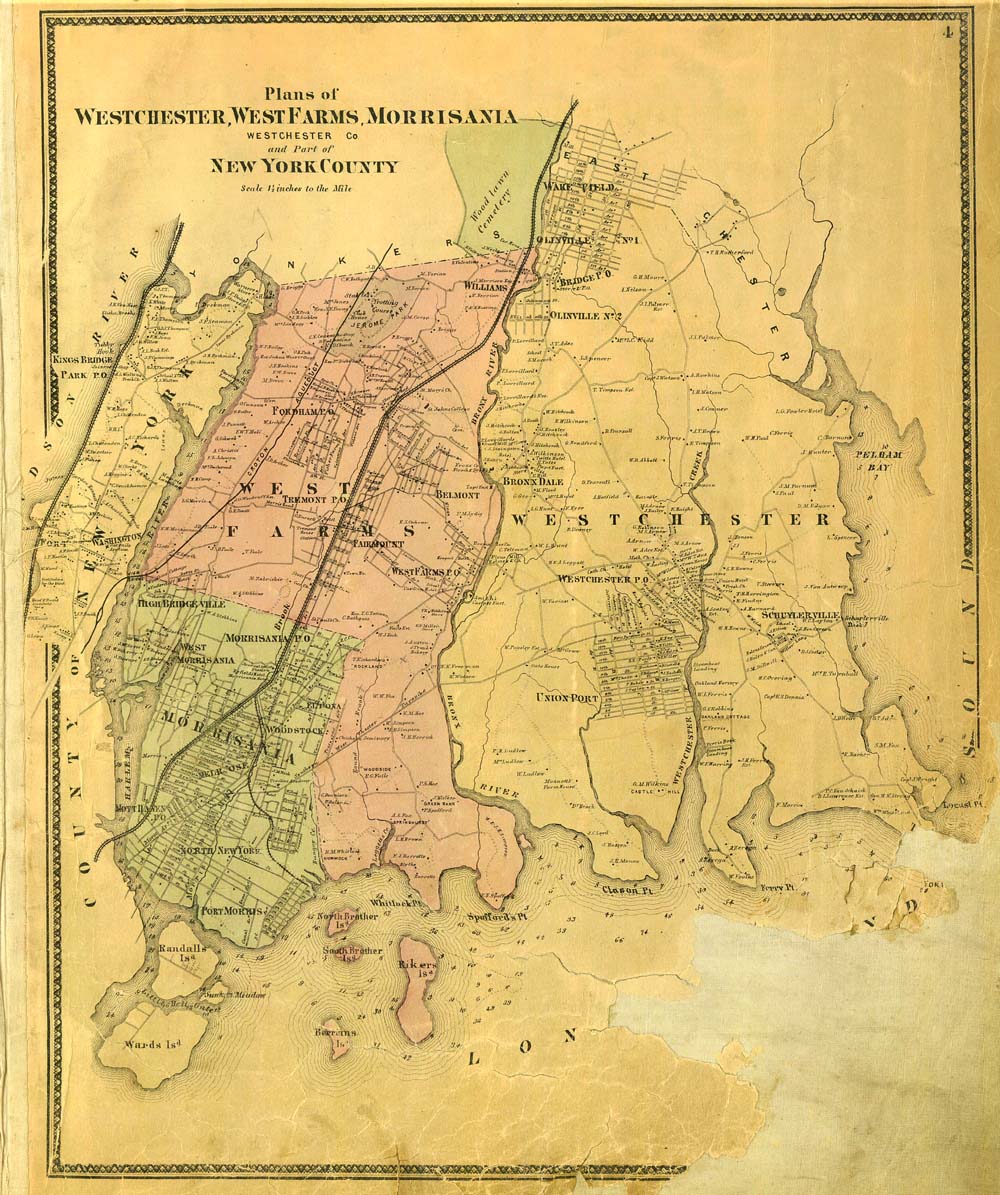

To understand the Bronx brewer, one needs to first understand why the Germans came to the Bronx, and to do that we need to look at German history. Like the Bronx, which began as individual estates and villages, Germany was for most of its history a loose confederation of duchies, principalities, and counties. Despite being briefly united under the Franco-Germanic emperor Charlemagne (742-814), Germany did not become a single nation until the nineteenth century.

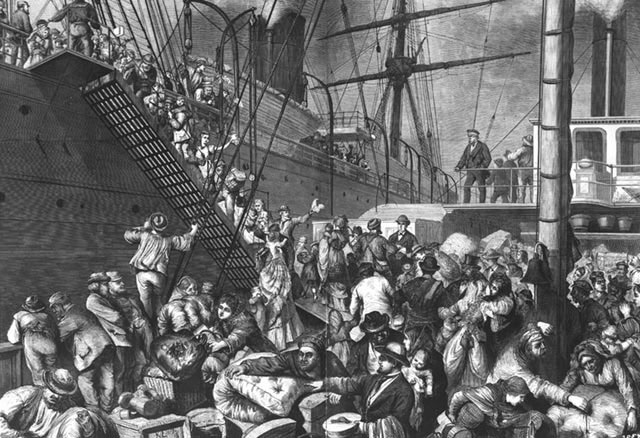

Plagued by internal power struggles, constant invasions, and wars, Germany did not begin to have economic success until its unification on January 18, 1871. German industrialization, however, began to take hold in the early nineteenth century, and as it grew, it created great changes in German society. The agrarian way of life was being transformed and people were forced off their land while violent revolutions were occurring all over Europe: millions fled.

Many Germans sought political freedom and economic success in New York. Fleeing the German revolution of 1848, they arrived in the city en masse. The entrepreneurial spirit with which the Germans (Christian and Jewish) impacted the industries of New York led to unprecedented success for a people who arrived with no economic advantages whatsoever.

The Germans contributed to Bronx industry and economy in three ways: one, they provided cheap labor; two, they became consumers; and the third and most important way was that they took the brewing of lager beer, which had been done in their homes in Germany, and developed it into a new and thriving industry in the Bronx.

The Bronx quickly adapted to the effects of the massive technological and transportation developments that accompanied and helped expand industrialization in America. These developments impacted Bronx urban life through beer and immigrant foodways. The term “immigrant foodways” refers to the foods or drink preferred by immigrant groups along with the circumstances under which these items are conceived, obtained, dispersed, preserved, prepared, and consumed. What people drink, when, and with whom is largely determined by both the culture they brought with them and the influence of their new environment. Foodways can also include new technologies that changed the trajectory of the industry.

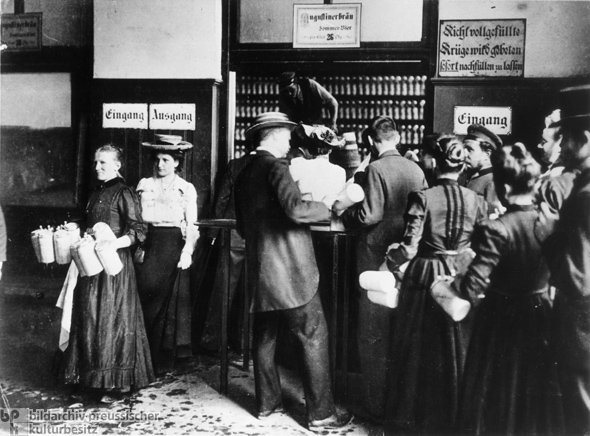

As circumstances allowed, Germans brought their food preferences and drinking customs with them to the Bronx, enabling them to maintain a sense of identity and cohesion by developing ethnic enclaves. From an immigrant’s outlook then, foodways occupied a central role in their assimilation. They served as instruments not only for routine nourishment, but for the preservation of memories of the world they had lost, and for the reproduction of tradition and community.

The Germans “disdained the weak American beer” so the ambitious took advantage of the cheap, wide-open spaces in the Bronx and opened breweries to produce their own ‘superior’ product.[1] New York’s local beer industry dated back to the Dutch settlers, but really took off with the nineteenth-century’s influx of German immigrants who brought with them the love of lager beer –and its fermentation secrets. Lager, was a lighter, lower alcohol beer and the New Yorkers who were tired of top fermenting ale loved it too. Lager is a fizzy, lighter, drinkable beer: “the mild pale-yellow beer soon accounted for four-fifths of the local beer production as it replaced heartier ales as America’s favorite carbonated lubricant.”[2]

Lager is a process, not a type of beer. The Germans had a knack for controlling the rot, which is what fermentation is. When it came to bottom fermenting lager beer, everyone joined in the ‘lager craze’. Drinking habits changed; the German brewers opened beer gardens, social halls, saloons, hotels, and casinos[3] where entire families, including women and children, were welcome to enjoy the Turnverein, elaborate gymnastic troops who entertained families while they enjoyed their lager. Germans drank less for sustenance and more for socializing, thus, they wanted a lighter, refreshing beer than the ale that was available.[4]

Along with the brewing industry, between 1840 and 1900, New York state was also the hop-growing capital of the country. In 1840, New York produced 447,000 lbs of hops, in 1899, 17,332,000!

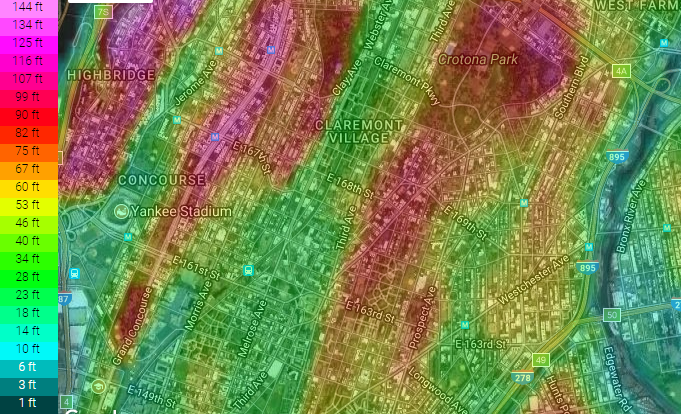

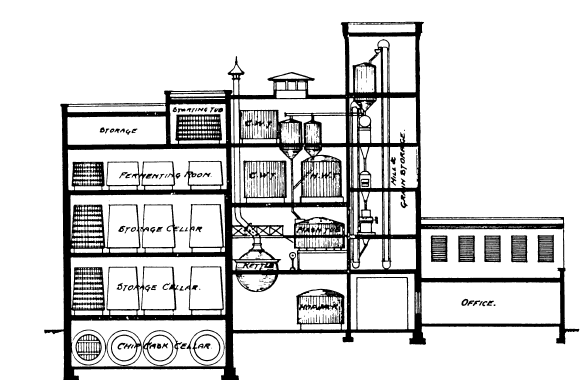

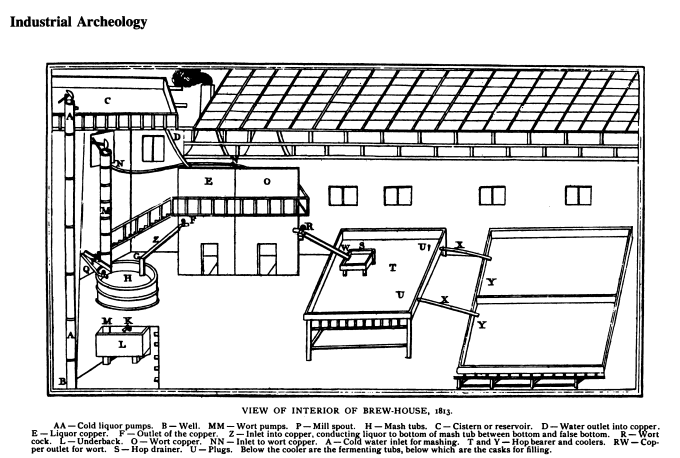

The Dutch were credited with introducing hops to New Amsterdam but the hop did not gain its importance until the English arrived. The main purpose for the cultivation of the hop was for its excellent use as a flavoring agent for beer. Lager beer requires a much slower fermentation, because it has to be brewed stronger in order for it to have a longer shelf life. It also requires a colder temperature than British ales. This would have presented a huge problem before the advent of ice machines , but the natural ridges in the Bronx terrain provided allowed for the digging of caves that would keep the fermentation process at the proper temperature. At home in Germany, they lagered (fermented) their beer in Bavarian caves, now, in their new home in the South Bronx they could utilize the same method. Aging beer in caves (or cellars) was also a traditional Belgian brewing technique, and was more common in America before the advent of modern refrigeration.[5]

In Brooklyn’s brewing industry, they had access to lake water from Long Island, which was both safe to drink and ideal for making crisp, refreshing lager. Luckily, the Bronx brewers had close access to the rail and the aqueduct, as well as many bodies of water where they could harvest ice locally, as well as ice blocks transported from upstate. Brewing lager wasn’t easy before refrigeration because these methods only worked in the wintertime. These were labor intensive and time consuming processes that did not work very well in the hot weather. So, when cooling machines were invented, the brewer’s limitations were solved. Refrigeration not only stimulated the lager-craze, it created an entire new ice-industry across the country. They no longer had to store their beer in caves or underground cellars and did not have to rely on the ice from local ponds.

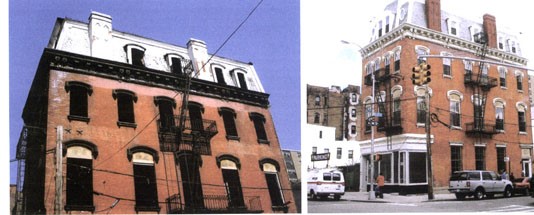

Another benefit to the Bronx brewers was the fact that New York water was clean, which improved the quality of the beer.[6] “By 1870, the town’s fourteen brewers found special locations. Due to the geographical necessity of brewing in the Bronx, breweries tended to cluster together. Restrictive covenants” precluded the brewers from opening their factories in several sections of Morrisania and that is another reason why the breweries were built so close to each other.[7]

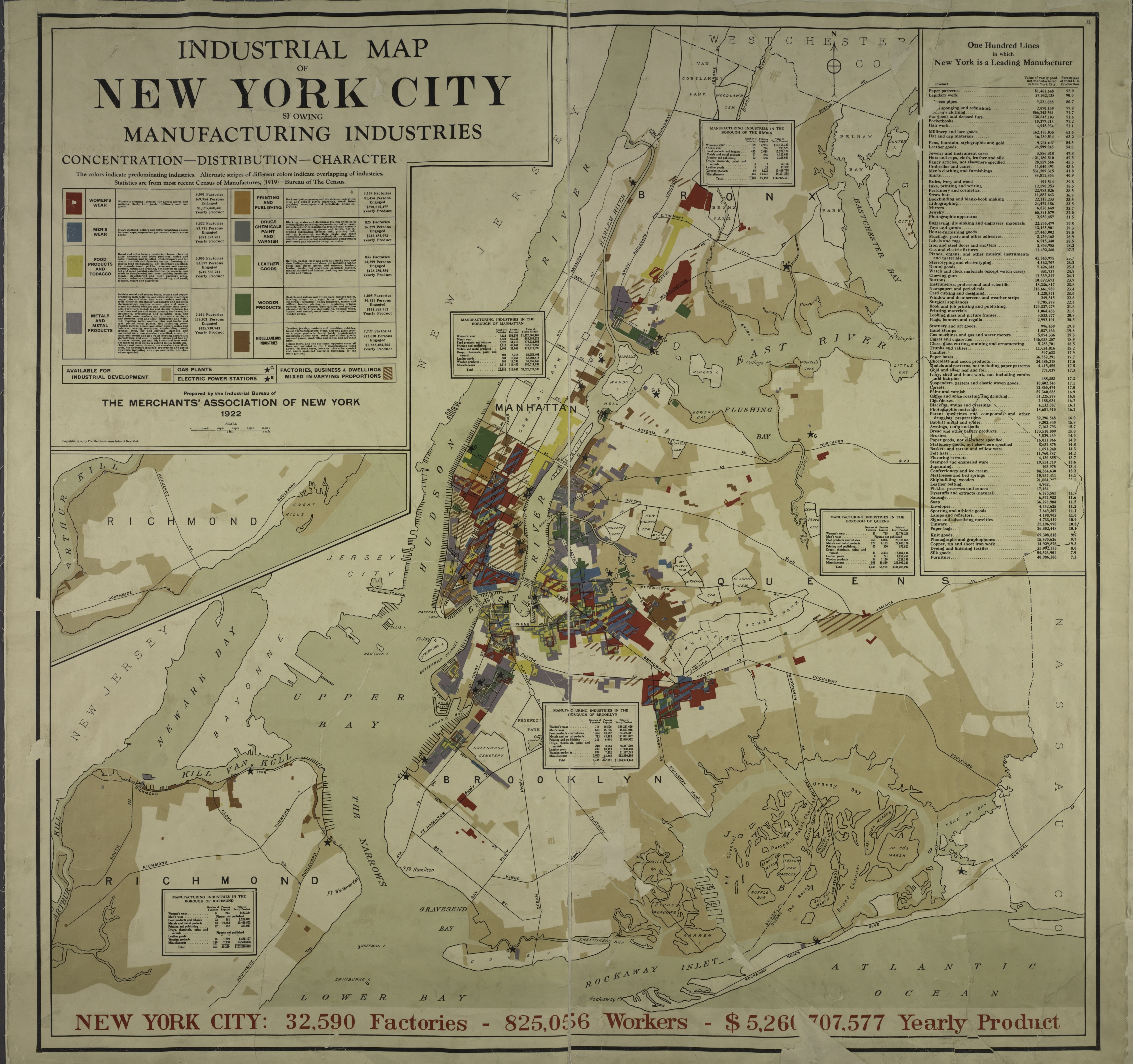

INDUSTRIALIZATION

The growth of the Bronx was directly influenced by the changes that resulted from the modernization of urban Gotham: it profoundly changed the Bronx’s existence from how and where people lived, as well as class development. The economic progress experienced during the years of 1885-1940 was unprecedented. We were becoming a consumer society; more income meant more consumption, which was good for the economy and the residents. With the advents of the rail, refrigeration, public transportation, ready-made clothing, packaged food, and labor-saving appliances, a higher standard of living was met; industrialization impacted the Bronx’s economy, ethnic foodways, as well as the public, and political ethos.

With the introduction of new machinery, rapid development and efficient production followed the technological and scientific improvements. Production was streamlined as the brewers were no longer hindered by the amount of work manual-labor provided. Beer production was also streamlined by the industrial development of the beer making process. Malting, coopering, and mashing were now done on-property as opposed to hiring outside specialists.

The breweries were more than an obvious physical development; they represented accommodation of an ever-growing population of different backgrounds, financial status, and the public services needed to make it work. The Bronx was filled with huge mansions and estates and were also surrounded by homes of lesser means.

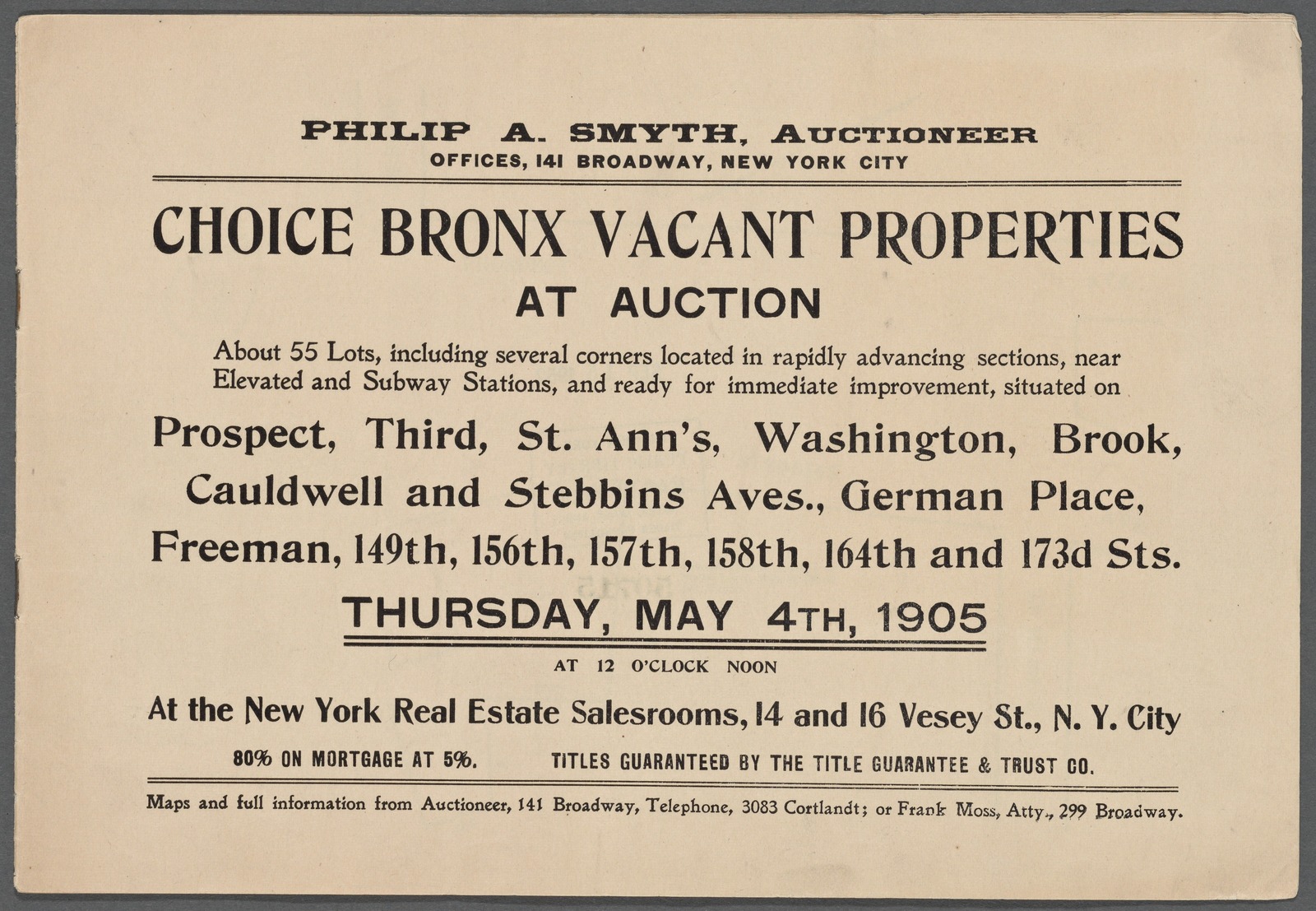

Morrisania’s powerful and affluent pioneers (often from the brewing families) encouraged the Bronx’s modernity with their technological advances in local infrastructure, machinery used in the engineering of canals and ports, Harlem River improvements, railroads and bridges, a subway system, and later, highways. As these circumstances allowed, Germans brought their beer preferences with them permitting them to maintain a sense of identity and cohesion while developing an ethnic enclave and beer industry. The main catalyst was modern transportation. In 85 years, over 250,000 miles of rail was laid, creating a national market. The Harlem Railroad gave the first push towards the real estate boom of the Bronx and as mass transit moved northward from Manhattan and a street plan was established, it attracted the immigrant population.

Eventually, the railroad eliminated exclusive markets and stimulated mass consumption. Business owners lost their local monopolies, but it opened sales nationally. One must remember that the cities that were associated with the changes in economy and values, were populated with people who were from older, rural societies and were quickly becoming increasingly urban. Thus, urbanization issues and the assimilating mass of immigrants from many different cultures, were another issue that shaped the relationship between business, labor, and the changes and effect it had on the individual. The public was forced to learn with the other and were thus, exposed to their traditions and new trains of thought. The development of the Bronx was directly influenced by the Bronx Breweries that created development, economic stability, culture, and the New York that we know today.

While making the affluent richer, the development of the Bronx still produced a great deal of benefits for the common people. Overall, the working class benefited from higher wages, more stability of employment, a greater choice in consumer goods, and economic growth. And it was these people who continued to vote for these policies and politicians for decades during the turn of the twentieth century. Ultimately, these were the businesses, the economy, the politics, the politicians, and the society that many people wanted, and that is perhaps the most decisive reason why it was so.

That which attracted the local brewers to the Bronx, was also one of the catalysts that killed it. When the rail expanded, so did the brewing industry. Throughout the 19th century, factories usually had to be built near shipping ports or railroad stops because these were the easiest ways to get factory products out to markets around the world. As more railroad tracks were built, late in the 19th century, it became easier to locate factories outside of city-centers. Streetcars helped fill up the empty space downtown where factories would have gone. Land was cheaper and the Midwest brewing industry boom arose as breweries implemented two innovative technologies: refrigerator cars and pasteurization. Both reduced transportation costs by preventing beer from going stale during transportation and these technologies allowed brewers to ship beer to distant markets. Despite the use of refrigerator cars, shipping beer in barrels was still expensive because breweries had to fill railroad cars with ice and set up ice depots along railroad lines.”[10]

In order for remote markets to be feasible, the destinations could not be far from the rail stops or the product would spoil during its transport; also, the destination had to be “large enough to compensate for the fixed costs of maintaining the ice depots required for beer distribution. Hence, refrigerators cars were mostly used to serve large markets along the rail network.”[11] Also, pasteurization permitted brewers to decrease refrigeration budgets and spread to markets “for which refrigerated transportation was not feasible.”[12]

The brewing industry in the Midwest was dominated by regional breweries who were participating in new bottling technology[13]and who took the larger scale markets, while the Bronx brewers were “dominated by local breweries using the production and distribution methods of the past.”[14] Distant locations were served using bottles —as opposed to kegs— because bottles did not require refrigeration while being transported, so their transportation costs were lower.[15] The Bronx’s industry was limited to the local market as their system was antiquated when compared to the Midwest.

[1] Jill Jones, South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City (New York: Fordham University Press, 1991), 19.

[2] https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/10/when-brooklyn-brewed-the-world/

[3] History in Asphalt, 476. Joel Schwartz, Community Building on the Bronx Frontier: Morrisania, 1848-1875, 61.

[4] William Bostwick, A Brewer’s Tale: A History of the World According to Beer (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), audio book.

[5] http://www.ediblegeography.com/bronx-beer-caves.

[6] Joy Santlofer, Food City Four Centuries of Food Making in New York (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2016), 243.

[7] Schwartz, 62.

[8] Playchan, 1969, 79.

[9] Hernandez Castillo, Carlos Eduardo. “Technology Adoption and Product Diversification in the Brewing Industry over the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” 2016, 3.

[10] (Cochran, 1948, p. 163; Plavchan, 1969, p. 81).

[11] Hernandez Castillo, Carlos Eduardo, 4.

[12] Hernandez Castillo, Carlos Eduardo,5.

[13] Hernandez 6.

[14] Hernandez10.

[15] Kerr 1998