Final Capstone Project for M.A in New York Studies.

The Bronx Was Brewing:

A Digital Resource of a Lost Industry

Michelle Hope Zimmer

I am lifelong resident of the Bronx and I constantly invite people to explore the “Northside”. You will not get a nosebleed –I don’t get the bends when I visit Brooklyn. Yet, one is more likely to meet a Bronxite in Brooklyn, than the other way around.

As a New York Studies major at The Graduate Center, CUNY, an interdisciplinary program (MALS), I wanted to immerse myself in my subject: The Bronx.

I decided that in order to accomplish a thorough interdisciplinary study of New York, I would need to challenge myself by taking doctoral history level classes, instead of only graduate level ones; I registered for as many classes that involved the subject of New York as possible in the history and art history departments, as well as the MALS program. Some of my relevant coursework was: Gilded Age/Progressive Era New York; Narratives of NYC; Wall to Wall New York: Muralism 1900-1940; History of New York City: A Political, Historical, and Sociological Profile; Urban Archaeology; The History of Modernity: 1789-1914; Social Matters: Architecture in the Welfare State. I led class PowerPoint presentations and wrote papers on: Immigrant Foodways of the Lower East Side; Woodlawn Cemetery: Modernity through Memorial; Ben Shahn: Photo-Muralist and Proto-Documentarian; Tenants, Moses, and the Heartbreak Highway; Junk Playgrounds; Manhattan’s archaeological sites; Fin de Siècle Vienna; and Crime, Prison, Melodrama, and Murals.

My research always leaned towards the immigrant experience, especially the Jewish émigré’s experience; often, it would be an underlying theme within my research papers. I was interested in what lured the immigrant to New York and how industrialization impacted the lives of the residents? How did new technologies change the trajectory of the Bronx, but mostly, why did it fail?

New York Studies is incomplete without a study of immigrants, for without them, there would be no Gotham. Whether poor, middle-class, or affluent, these cultures pollinate that which makes New York City what it is: a little bit of everything. My initial goal was to study The Bronx through the lens of literature and film, art history and sociology, architecture and archaeology, its foodways, and immigrant cultures —which I soon realized was too broad in scope.

After meeting with my thesis adviser, Dr. Cindy R. Lobel, a New York food historian (with whom I also studied history during my undergraduate studies at CUNY Lehman College in the Bronx) I knew I would choose the modern approach with a digital history Capstone Project, instead of a written thesis on the Bronx. Dr. Lobel thought that something involving a map would be a good idea and so did I. I love a challenge and I am quite creative… but why would I choose a digital project whilst not having had taken any digital classes? How would I find the time to learn how to do it, build it, and most importantly, do the research? As a historian, it was imperative that my research not suffer.

I attended the CUNY Geographic Information Sciences (GIS) Summit where I was inspired by a lecture given by the Vice Provost of Research at Bronx Community College, Sunil Bhaskaran. I was pleased to learn that he is spearheading a geospatial technology movement up in the Bronx.[5] I left the symposium inspired but with the sobering feeling that my scope was too broad and needed to be more specific. I consulted with digital librarian, Stephen Klein and he directed me to helpful websites as well as the New Media Lab for more exhaustive support. Stephen Zweibel, the data and digital projects librarian for Digital Humanities, told me that “I was scaring him” when I explained the scope of my potential project, followed by my lack of expertise.

So, I focused on my research: Bronx Style. Since Bronx digital research has not yet caught up to Manhattan, I started out by taking to the streets and visiting the areas of my past research in MALS to see what would inspire me. My guerrilla investigation always brought me back to the south Bronx. This is when I discovered Brewery ruins on St. Ann’s avenue and 160th street; the only nineteenth-century Bronx brewery that still (barely) stands. I channeled Indiana Jones and Lara Croft and continued my adventure. The gruesomely beautiful edifice was the ruins of the Hupfel brewery.[7]

Bronx Breweries. I had no idea.

I decided to focus on the brewing industry.

Many people have a short memory when it comes to the Bronx. They are surrounded by history and are unaware. With a bit of preliminary digging I learned that several breweries were in the Bronx. Like most people, I always thought of Brooklyn, the upper east side of Manhattan, and, of course, the Midwest when I considered the brewing industry, but as with most successful pioneering industries, they had their start at a smaller level here in the Bronx.

My goal was to create a digital resource on the Bronx breweries; first, I learned where the Bronx breweries were, by finding examples on old maps and atlases, and created a map of markers to show where they were on a modern map. It was also important that I learn a bit about these brewers as I am a cultural historian, not a digital cartographer, which is included on this site.

I returned to the Hupfel Brewery ruin to take photographs and I befriended a kind military veteran working on his truck in an alley way (featured in the video included on this website), I dodged what sounded like a puppy-mill, and what smelled like the urine soaked alleyway that it is, and had my partner, Jonathan, climb an outdoor fire staircase (with permission) to the roof of an adjacent building to gain a different perspective on the brewery and its relation to the ridge and the former Ebling Brewery which was just two blocks south. These images are included on the site. Both breweries were built at the base of a steep ridge perfect for cave lagering their beers.[9] And apparently, also perfect for an art exhibition. In 1964, the Ebling caves inspired the final “environment” of an art exhibition called “Eat” by Allan Kaprow.[10]

The caves sat covered, until recently, when developers needed to fill the caves for foundational support for the construction of a massive apartment building. It is unfortunate that the caves were not saved. They would be a great location for a grotto themed restaurant, fungus farming, or (of course), beer!

Tenements were built around the periphery of the Hupfel factory and the edifice was left to the elements where it devolved to an urban Angkor Wat; where there was once only brick and mortar, one now sees trees growing out of the window frames. The top floor looks like an accidental greenhouse. This block is a bizarre juxtaposition of the modern city and the dilapidated factory. I documented everything through photography and compared the shots to atlases, the Bronx Board of Trade’s archives, newspaper articles, and the NYPL’s digital photography collection.

When I returned to Morrisania to visit the most popular brewery block, Third Avenue between 168th and 170th streets, I found a low retaining wall that looked quite old. One of the bricks was loose and I learned that it belonged to Henry Mauer a German born producer of fireproof bricks who was known to build brewery factories.[11]

Adjacent to this wall was another ridge. I would love to learn if they hide more caves ( perhaps, the Eichler caves). All Bronx Breweries have been razed except for the Hupfel ruin. If this wall is what I think it is, then I found a section of either Kuntz, Mayer, or Liebman (producers of Rheingold) Breweries.

While interning at Woodlawn Cemetery I did research for their head historian, Susan Olsen, on a project called “Faces of Woodlawn” where I researched the portraits of the interred and the artists who created the marbles, busts, statues, bas-reliefs, and bronzes. Olsen wanted to know what if any their connection to the artists were and New York history. I recalled a picture I took of the Ehret mausoleum.

George Ehret of Hell Gate Brewery was one of the two most famous Manhattan brewers. Although, not a Bronx brewer, he did own a ferry business out of Point Morris in the Bronx. However, there is another important connection, he learned the trade and started his career working for Adolf Hupfel, mentioned previously. I contacted Ms. Olsen to see if there were any other brewers form the Bronx besides Ebling and a couple of others mentioned in McNamara’s study and she immediately replied with plot information about almost every brewer on my list. There was my Woodlawn connection! Remarkably, the same brewers who owned factories next to each other, were also buried next to each other. This was remarkable. She called it “brewers row”. Olsen immediately set me up with a historian and civic planner Nelson Valyduk who gave me a private tour of the Brewer’s sites. These brewing Families are like a soap opera. They intermarried and apparently rest eternally with each other too. It gets a bit confusing.

Most helpful in confirming modern addresses for nineteenth century factories and beer gardens was John McNamara’s research for the Bronx Historical Society in A History in Asphalt where he lists all of the former street names which was useful in mapping breweries on a contemporary map.[12] Many of the street names have changed. Another effective source was Joel Schwartz’ dissertation, Community Building on the Bronx Frontier: Morrisania, 1848-1875. This source helped shape my understanding of early Morrisania. A most helpful find was William McGuirk’s thesis A History of the Bronx Breweries: 1860-1900, inspired by the death of a relative in Guinness’ Dublin plant, McGuirk, focused on the brewing science, labor history.

My Capstone Project’s focus is to create a digital source and is more of a cultural history focusing on the beer industry of the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century, when Prohibition killed it. My initial goal was to create a mapping resource. This idea was outside of my mapping expertise (none) and I decided that it was that a general history would be a better idea. When I delved deeper into the subject, I learned that there is a thesis from Cornell University written in 1990, Something is Brewing in the Bronx: A History and Rehabilitation Plan for the Ebling Brewery, by Sylvia Rose Augustus. She focused on what would be needed to reopen a microbrewery where the Ebling Brewery used to operate. Augustus, examines the history of brewing technology and explores the possibility of reopening the abandoned Ebling Brewery. A moot cause, as there now stands a newly constructed apartment complex, so it apparently did not come to fruition.

Two other invaluable resources were the Successful, German-Americans and their Descendants and especially History of the Brewing Industry and Brewing Science in America, Prepared as Part of a Memorial to the Pioneers of American Brewing Science, Dr. John E. Siebel and Anton Schwarz, 1854-1931.

I also spent several few weeks reading the ads and listings in old phone books that are available in microfilm at Lehman College.[13] I wanted to see how many breweries remained and what line of business they were in during Prohibition. I spent a month getting vertigo in the periodical room at Lehman College, racing through miles of reels. Ed Wallace the periodicals librarian was helpful and gave me access to their immense collection, at my leisure. The Bronx Special Archive’s historian and librarian Dr. Janet Munch was extremely accommodating, she sent me numerous emails with links, met with me on countless occasions, and gave me historian Lloyd Ultan’s phone number. I had been following his career for many years and I was excited to finally meet the official historian of the Bronx. I was given his home phone number. Not unlike my experience researching Bronx sources, Mr. Ultan is also in need of digitization: he hates email. He immediately made plans to meet with me at the Bronx Historical Society where we talked for hours while perusing sources including The Atlas of the Borough of The Bronx by Hyde & Company, 1900. Seeing the atlas in person is incomparable to viewing in online. I was able to make sense of redundancies as several brewery names had the same addresses. I was also able to confirm if any of the German brewers were Jewish (David Mayer) and if so, where was their house of worship –something I disregarded on the computer screen but was able to find in person, a building near the Zeltner, Eichler, Mayer, and Kuntz breweries was the original Agath Israel, a synagogue easily missed as it is marked as a “church”.

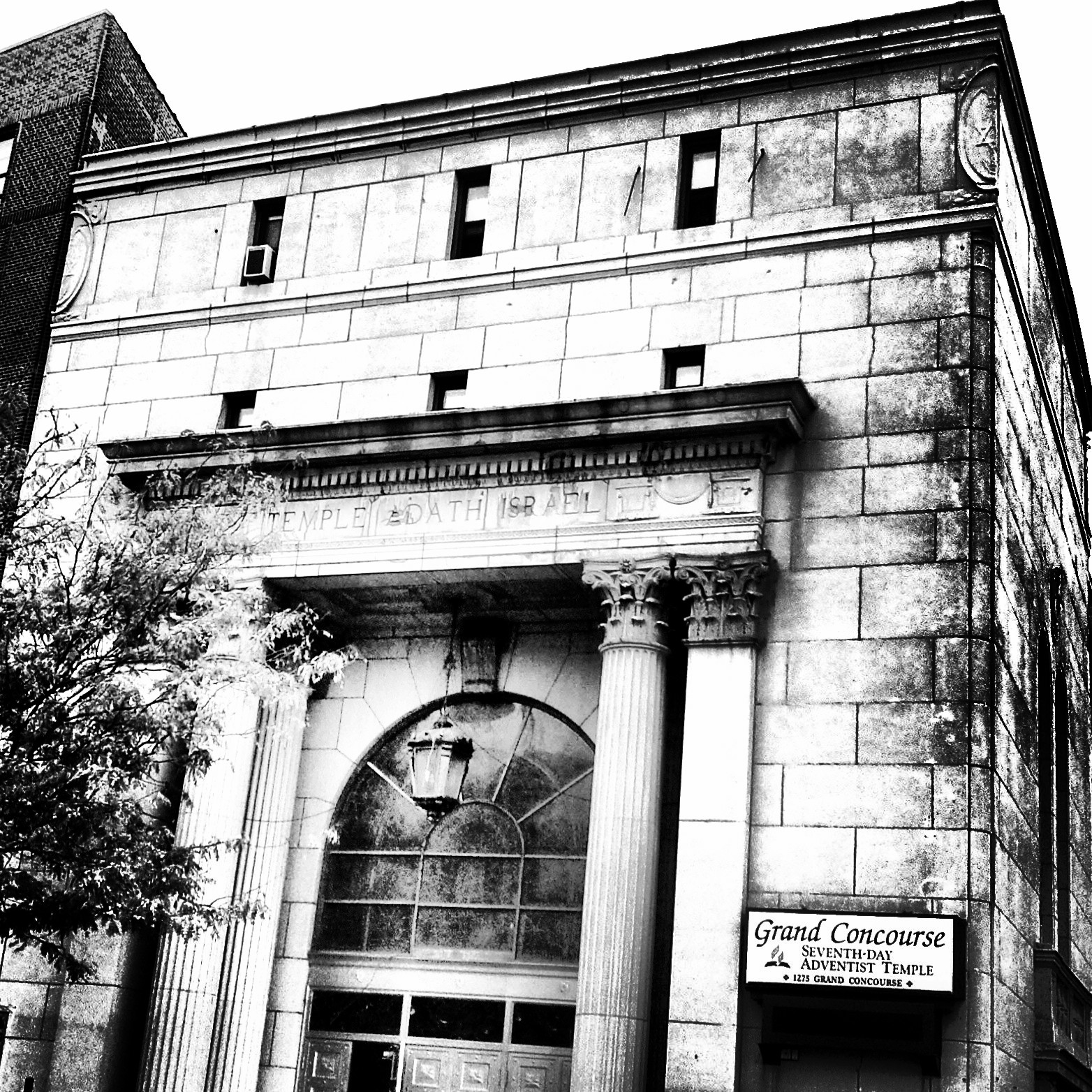

Often, I found connections to my research. My dad became a bar mitzvah at Adath Israel at its second location on the Grand Concourse (now a Christian church), which subsequently moved to Riverdale, where I live, and where my family has numerous memorial plaques! My uncle has been running their weeknight minyans for over 35 years.

Finally, ready to begin the digital side of the Capstone Project, the New Media lab at The Graduate Center, CUNY, concurred with Stephen Zweibel that I should start with Leaflet Map Markers and later, as I collect more information and digital expertise, add to the site. I decided to take advantage of CUNY Academic Commons and build a WordPress site through one of their themes, choosing Klean and then changing it to 2016. I had plenty of formatting problems and was driven to tears more than once: videos were not working, fonts were unable to be seen with my background image choice, menus were invalid, and many other issues. Most recently, losing a week’s worth of pages.

Before I returned to school, I had over 20 years of intensive hospitality experience managing some of NYC’s top-rated restaurants, I was not just a bartender, I was a farm to bartender who taught the staff about our products. As an amateur historian, I taught classes to my staff on the history of our products. I was always intrigued by beer’s broad and long history. As a wine drinker, I was fascinated by beer. Because, as I heard from many of my former restaurant owners, “wine happens but beer is made”. Still, in embarking on this capstone project, I needed to cover a lot of ground: from understanding the lagering process and how it was different from ale, to the history of Morrisania settled by the famous Morris family and the powerful productive people who settled the area known as the 23rd ward, to factory architecture and immigration, and World War I and Prohibition. Finally, I needed to include the recent renaissance of craft breweries.[14]

And somehow, take this massive amount of information and make it available to the lay person via concise summaries and images on this site.

While in the MALS program, I immersed myself in the subject of New York Studies from many angles. I developed a massive library of primary, secondary sources, articles, and personal research. My understanding of New York history has been enriched by the interdisciplinary scope of my courses. Through each stage of my research, I attempted to view the source through the different prisms of study I experienced in the MALS program. My research has unearthed numerous potential avenues of study: gender/urban studies, industry, advertising, technology, slavery, sociological, economics, politics, foodways, employment history, union development, immigration, Jewish history, art history, death rituals, and science, to name a few of the potential themes of scholarship the Bronx breweries can inspire.

I also revisited the sources from Professor. Thomas Kessner’s New York History and Gilded Age and Progressive Era syllabi, as well as numerous resources available in the CUNY Graduate Center’s and Lehman College’s libraries about New York. The notes in Evelyn Gonzalez’ The Bronx were and are a source that I have used in almost every MALS class I attended. I reviewed Dr. Marta Gutman, Dr. Singer’s, and Dr. Lobel’s readings and made a connection to the German ethnic enclave in the 23rd ward and the cultural mix that mingles with other cultures to form new norms which metamorphosed into something new and current to their time.

The brewers had the right temperament for success in the Bronx. A Bronxite must have a resilience that he either possesses, or a resistance he acquires. The emotional and psychological temperament of New York City can be volatile, not the New York of Edith Wharton but having more in common with Crane’s Maggie. According to E. B. White, New York can either destroy or fulfill an individual, as if by pure luck.[1] But, I would posit that German brewers made their luck.

A New Yorker is someone for whom the pull of New York is stronger than the push. And indeed, the Bronx often shoves the fainthearted right out of town. To be a New Yorker, or someone who understands what it is to be one, one needs to grasp the meanings and dualities of the big city; that which is normally perceived as empty and absent of any civilized qualities to the outsider, can be translated into something productive to the successful New Yorker. As remarked by E. B. White in Here Is New York, a New Yorker understands that the “gift of privacy” can also be a “jewel of loneliness”[26], that “magical occasions are free” but normal frustrations are amplified.[27] One must find balance to survive. Even when E. B. White struggled to support himself, even when New York City “hardly gave him a living, it still sustained him”[28] because New York feeds the soul, and can even be a substitute for one that is lacking.

Native New Yorkers are born with an urban armor, and those who relocate to New York (attempt to) develop one through an urban osmosis of sorts. A successful transient, in this case, the German brewer, manages to keep the “old culture and the street-wit of the new.”[29] The German brewer was successful because he felt that he had the right to succeed and was entitled to the “resources that the city embodies . . . it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire.”[30] And he did it by hard work, and by earning power through the local government.

The Bronx represents a tolerant elsewhere, where the unity of many cultures, politics, and values (often lack thereof) offer one an escape from his or her past with opportunity to create a new future. New Yorkers are not local, they are global. In fact, its tradition is the tradition of traditions, as all the influences in New York culture come from somewhere else –or were pioneered there. Yes, this may describe most places, but what makes the Bronx different is that here, there are many more types of cultures found and in a much closer proximity to one another.

Tolerance is a function of uncertainty and since anxiety is a recurring presence in the Bronx’ multi-cultural society, they became tolerant by disposition and necessity.[31]

It comes to life in every dimension and transcends barriers of the imagination. It is more than a city and home; it is a partnership of chaos and restraint and it requires a balance of both control and instinct. One cannot be effective and useful without the other. New Yorkers are shaped by many things: ethnicity, socio-economic identity, and gender identity; there isn’t one New York identity other than the necessity to obtain a thick-skin.

A common theme seen in Dr. Kessner and Dr. Lobel’s New York classes were the identities of the New Yorker. What makes the New Yorker? My focus on the Bronx has been influenced by ethnic identity, socio-economic identity, as well as gender identity: there is no single identity. Due to the United States’ history of immigration, the United States has never developed a singular recognizable identity. However, there are subcultures found in ethnic enclaves that serve multiple purposes: they offer a foundation that bridges the unknown to the familiar resulting in open-minded acceptance of another culture with the familiarity of their own, thus encouraging diversity… sometimes at the expense of losing its specificity.

I applied this to my understanding of the German enclave of Morrisania and it helped me focus my research to learn the impact the brewing industry had on the neighborhood. From employment, to language, to entertainment (beer gardens), and housing.

Ethnic enclaves often cross over boundaries and infuse with other cultures resulting in a local creolization niche as well as an economic opportunity outside of their original culture. Sometimes this is a slow process. The borders bounding ethnic enclaves have never been static or resistant to the motivated “national corporations, ethnic businessmen . . . clients”[32] and diverse customers who traversed their boundaries.

In the early twentieth-century, many transgressed these cultural borders resulting in a “particularly intensive phase of cross-cultural borrowing.”[33] This was an effect in my focus too. Non-Germans drank Lager, ate their cuisine, and picked up on the language (e.g. delicatessen). During these years, their enclave clientele, sought new consumers in their multi-ethnic urban and regional markets creating specialties within their trades. These niches included advertising ethnic foods (beer) and adapting them for the general public. Thus, influencing New Yorkers from other cultures which they then blended with their own customs to create novel experiences. The growing number of immigrants, and their cultural difference . . . led many Americans to fear that they would lose control of their cities and even the whole of their society.”[34] There were even hostilities within the same religions. For instance, many German-American Jews who arrived much earlier than the eastern European orthodox Jews whose “foreignness” (or reluctance to assimilate) offended the already assimilate German Jews.”[35] They were blamed for American anti-Semitism.

This project is evolving; there are many more bells and whistles for me to learn within the mapping technology as well as the site itself. Once I can broaden my digital knowledge even more, I want to get started on more map layers. The second layer will be focused on the beer gardens, saloons, restaurants, and casinos of not just the 23rd and 24th wards, but the rest of the borough too; followed by a layer that will concentrate on the archival news stories that I collected of the bi-products of the Temperance Movement and Prohibition: the numerous arrests, padlocking of breweries, lawsuits, and organized crime. The fourth layer will focus on urban archaeological sites and the beer related artifacts found.

Prohibition and the industrialization that expanded the industry westward brought an end of an era and a way of life for so many Bronxites whose livelihoods depended on the beer industry. Today, there are three breweries in the Bronx; between 1848 and 1920, there were approximately 18. The Bronx was, and now, also is brewing.

“The American brewing industry reached another milestone at the end of June, with more than 3,000 breweries operating . . . Although precise numbers from the 19th century are difficult to confirm, this is likely the first time the United States has crossed the 3,000 brewery barrier since the 1870’s . . . the Internal Revenue Department counted 2,830 “ale and lager breweries in operation” in 1880, down from a high point of 4,131 in 1873 . . . While a return to the per capita ratio of 1873 seems unlikely (that would mean more than 30,000 breweries).”

[1] Sara Rimer, “Once-Decayed Bronx Neighborhood Surges With New Energy,” New York Times, Aug 7, 1990, B1.

[2] Joel Schwartz, Community Building on the Bronx Frontier: Morrisania, 1848- 1875. Dissertation. Department of History, 1973. Lloyd Ultan and John McNamara have written numerous books on the Bronx with mentions of the breweries, but a modern detailed study of the beer foodways of the Bronx has not yet been done.

[3] John McNamara, History in Asphalt: The Origin of Bronx Street and Place names (New York: The Bronx County Historical Society, 1991), 243.

[4] The term “immigrant Foodways” refers to the foods preferred by immigrant groups along with the circumstances under which they are conceived, obtained, dispersed, preserved, prepared, and consumed. What people eat, when, and with whom is largely determined by their culture and the influences of their new nation’s culture, in this case, The Bronx. Foodways not only refers to food and cooking, but to all food-related behaviors, as well as new technologies that changed the trajectory of the industry. By analyzing the history of brewing in the Bronx, it can relate to greater topics in New York history. Bronx culture was built on the food prepared by mothers, local retailers, and later, huge food conglomerates. One can only prepare what is available, and slowly, everything became available. As circumstances allowed, immigrant groups brought their food preferences and eating customs with them to the Bronx, permitting them to maintain a sense of identity and cohesion while developing ethnic enclaves. From an immigrant’s outlook, foodways occupy a central role in their assimilation, both as an instrument for memories and loss, as well routine nourishment and the reproduction of tradition and community.

[5] http://www.bcc.cuny.edu/geospatial/?p=gcci-Faculty-and-Staff

[6] http://libguides.gc.cuny.edu/digital_tools_consult

[7] Bought in 1863 but built in 1848.

[8] Beer with low alcohol content.

[9] William McGuirk, A History of the Bronx Breweries: 1860-1900 (Lehman College, 1996), 47. John McNamara, History in Asphalt: The Origin of Bronx Street and Place names (New York: The Bronx County Historical Society, 1991), 210.

[10] Michael Kirby’s article about Allan Kaprow’s art installation “Eat” can be found in the Tulane Drama Review (Volume 10, Number 2, Winter, 1965).

[11] https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4f75-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 http://brickcollecting.com/collection2.htm Mayer and Eichler breweries both suffered from several fires over the years..

[12] History in Asphalt: The Origin of Bronx Street and Place names, 378. Fordham Avenue was the former name of Third Avenue

[13] My paternal grandfather’s upholstery business, as well as my father’s childhood home were found in one from 1929.

[14] Bronx Brewery responded to my inquiry and will be providing me with a private tour in the near future.

[15] Carl E. Schorske, Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), Introduction.

[16] Fin-De-Siècle Vienna, Introduction.

[17] Schorske, Chapter II, “The Ringstrasse, Its Critics, and the Birth of Urban Modernism”.

[18] Henri Lefebvre, Ed. Lukasz Stanek, Towards an Architecture of Enjoyment (London: University of Minnesota Press).

[19] David Harvey, “The Right to the City” New Left Review, 53 (September-October 2008), 1.

[20] Harvey, “The Right to the City”, 1.

[21] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (NY: Vintage, 2011), 280.

[22] The Warmth of Other Suns, 280.

[23] Ibid.

[24] David Harvey, The Right to the City, published in New Left Review 53 (September-October 2008), 1, 2.

[25] E. B. White, Here is New York (New York: Harper & Bros, 1949), 696.

[26] White, 703.

[27] White, 709.

[28] Ibid, 703.

[29] Ibid.

[30] David Harvey, The Right to the City, published in New Left Review 53 (September-October 2008), 1, 2.

[31] White, 707.

[32] Donna R. Gabaccia, We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 94.

[33] Gabaccia, We Are What We Eat, 94.

[34] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the Making of the Gay Male World,1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994., 137.

[35] Chauncey, 105.

[36] McNamara, Asphalt, 486.